Suddenly, as soon as the first piano notes are heard, a hysterical frenzy transcends the venue: musicians waddle onto the stage, dancers rush on the dancefloor, their patent shoes gliding on the lacquered wood flooring, and everyone sings along to the rhythm of “Haaa… bi-bi!”. Each performance brings the same madness, and night clubs all over New York are shaking.

Joe Cuba’s sextet skyrockets to fame with their new song, cunningly named « Bang Bang ». Many similar deflagrations would soon shake ballrooms across the Big Apple. Over the year 1966, a new pulse spreads like wildfire on the sidewalks of Spanish Harlem and local radio waves.

“This is boogaloo”, you could hear. Like no music genre ever before, it brought together African Americans and Latinos. The two communities had been attending the same parties for a while, but they wouldn’t boogie to the same tracks: as Black people waited for the rhythm n blues and soul tunes, Latinos saved their energy for the cha-cha-cha and pachanga.

As the ultimate musical syncretism of popular genres in the Barrio, boogaloo is often described at « the first Nuyorican music ». Purists claim that you can hear the premises of the genre in the cover of “Watermelon Man” by Mongo Santamaria, or in Ray Barretto’s “El Watusi” in 1963. But it is in 1966 that it established itself as the most vibrant incarnation of its time, both musically and politically.

A revolutionary hurricane was then blowing on Amerika: in the trail of the Black Panthers and the Young Lords Organization, minorities were gathering in the streets to reclaim their rights from the establishment. The apparent naivety of the lyrics of the hit “I Like It Like That”, recorded by Pete Rodriguez’s orchestra for Alegre Records in 1996, is misleading: it must be interpreted as the most direct and dazzling affirmation of an identity.

Blacks and Hispanics were now embracing their skin colors and origins, while asserting their American identity. Boogaloo made it way on the soundtrack of a social revolution overtaking the country, and lend it its tempo until the end of the decade, before it got overshadowed by salsa. « Boogaloo is youths trying to make it, it’s immigrant influence, it’s musical development.”, says Johnny Colon in the must-see documentary We Like It Like That.

Boogaloo’s energy seduced young people from different backgrounds, well beyond the borders of the U.S.A., and especially in the Caribbean cradle land: in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Dominica, and all the way to the French West Indies. From Fort-de-France to Pointe-à-Pitre, old biguines and mazurkas from West Indian orchestras strong of a bloodline of virtuosos, from father to son in the likes of Siobud, Stellio, Fanfant or Coppet, became outdated by those modern beats.

When boogaloo overtook the West Indies, at the same time as other music genres with amplified keyboards and electrified guitars, this new wave knocked out hierarchy and habits. The necessity to learn how to read music to call yourself a musician became obsolete, as you only needed a good pair of ears and to be tuned on the new sounds from the international radios.

“I was a student in Paris in the early 60s”, recalls Fred Aucagos, Guadeloupe’s first rock musician. But I didn’t go much in class, I was hanging out with Golf Drouot, with Eddy Mitchell, Johnny Halliday, Dick Rivers… When I went back home in January 1966, I brought back on the island the first reverb amplifier and the first electric guitar. I was yé-yé, I wanted to play this music home.”

Aucagos started by revisiting the standards of French and Yankee rock, but the musicians in his band, the Vikings of Guadeloupe, persuaded him to sing in Creole, to add some ka drums, hire some Latin brass… On Fred Aucagos’ “Ti Man’zelle”, we can hear a subtle mix of imports from the mainland, the U.S.A and the neighboring islands. With only one desire in the end: fire up the West Indies balls.

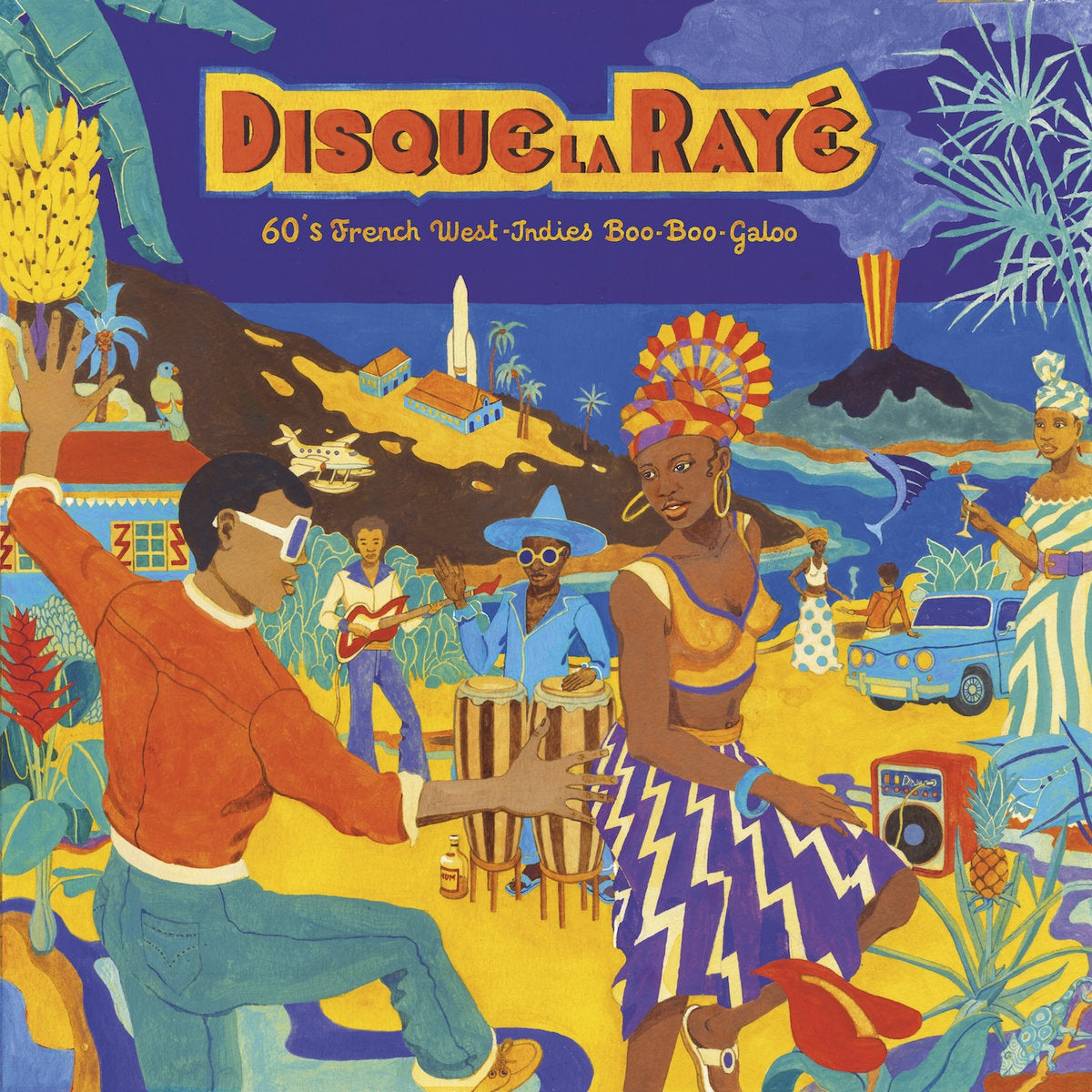

On the dancefloors of the most prestigious nightclubs, such as La Bananeraie in Martinique or La Cocoteraie in Guadeloupe, musicians dabbled with boogaloo coming up with rather unorthodox interpretations, and this is precisely what gives this compilation its singularity and panache. It incorporates influences from the African continent thanks to the Rico Jazz (an adaptation of “Si Tu Bois Beaucoup” of the Congolese rumba orchestra O.K Jazz).

It rubs elbows with the “Jerk Vidé” of a David Martial before he turned in a doudouiste cliché. With the cheeky humor of the Guyanese Dany Play (“Mais Tu Sais”), the perkiness of Joby Valente (“Disk La Rayé” with Camille Soprann’ on sax), we (re)discover forgotten classics published half a century ago on the two historical labels in Guadeloupe: Aux Ondes of producer Raymond Célini, and Disque Debs whose boss Henri Debs can be heard behind the mic on “Ou Pas Z’ami En Moins”.

In another style, “Ou Que Di Moin” from Monsieur X is a Creole funk pamphlet, neither Latin, nor festive, and not strictly boogaloo for that matter. The Nuyorican rhythm is a tiny fraction of what the West Indies orchestras were playing, and they would often incorporate biguine and Haitian kopi elements. This compilation allows some deviations, for the fun of it, presenting tracks where boogaloo is more of an influence.

Assisted by Jean-Baptiste Guillot of the Born Bad label, Julien Achard spent more than three years digging some records to compile the best of the Creole boogaloo. The charm of the restored sound of these old 7” vinyl records is only matched by the ardor of the interpretations. “Sauvagement sexy”, wildly sexy, as Gabby Siarras sings.

David Commeillas

Read Less