“Qui c’est celui-là?” Many French asked themselves this question (“Who’s that guy?”) when the song bearing this title began to smash the hit parade in 1975. Some others already had parts of the answer: it’s the guy who sang “Amour amitié”! The guy who sang “La femme du sergent”! The guy who sang “Armand” in “Le Petit Conservatoire de Mireille”! To all those French, Vassiliu had always been reduced. Few were the real fans, who had explored all angles and taken the measure of the man.

Vassiliu was – awful word – a poet. Even worse, he was an wandering entertainer. He wandered the world, bringing back words, sounds, instruments and feelings. Maybe his rhymes weren’t that rich, the instrumentation not too lush, the production quite laid-back and the timbre rather little demanding, but you could be sure the song would be pampered. Had anyone else taken care of it, it would have been worse. To make a good Vassiliu song, you had to be Vassiliu. The problem is, all this was nothing but a succession of misunderstandings. Because he continuously tried to remodel his career, from a chansonnier to a cunning singer, from tender to comical, to a beatnik poet, to an ethno-artist, to a venue manager, to a showman, to a barfly.

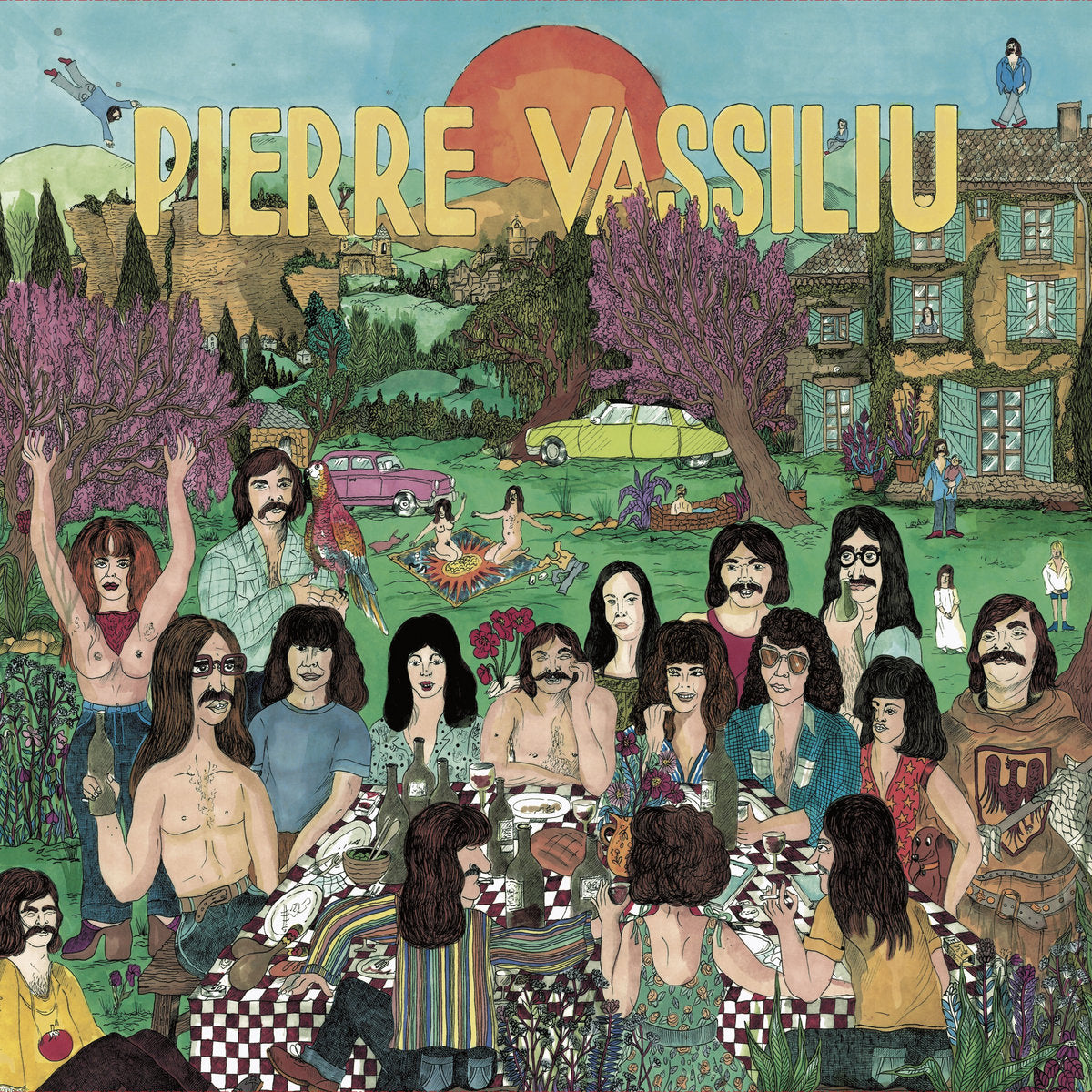

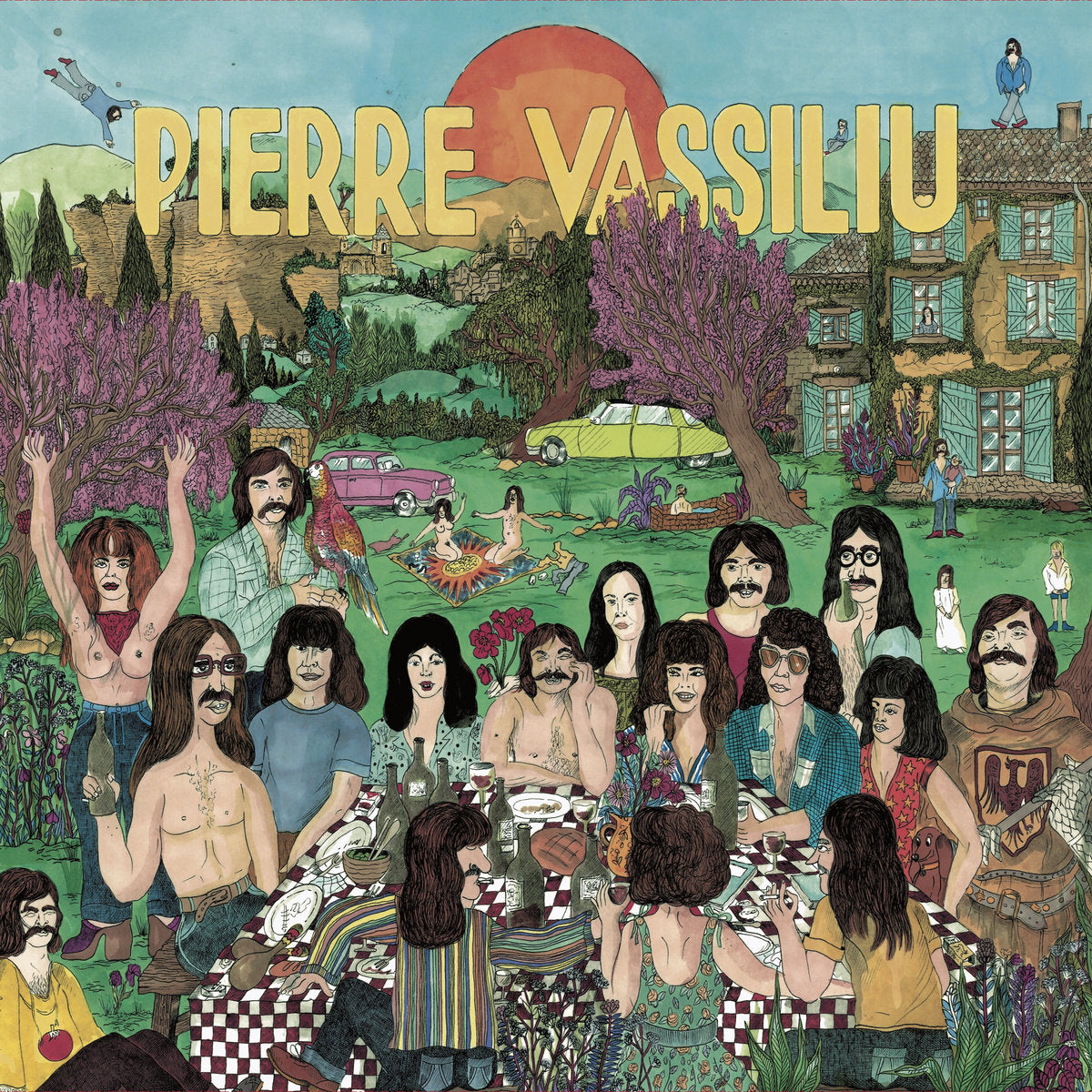

1961. Pierre Vassiliu, a horserider and a war photographer, embarks with his brother Michel (lyricist) in the music business. Their department: comedy. Puns, a funny voice, honk-honk and oompahs. Lucky break, it works. A first misunderstanding gets him labeled as an agitator: his song about the military is censored on the radio, and only played past midnight. That’s all it takes to create a buzz. Georges Brassens champions him and writes a few laudatory lines on his first 45 – Vassiliu is launched. But enough with the smutty rhymes designed to make lowbrows laugh. The sassy man sets to putting sweet songs on his singles, such as “Le Manège désenchanté” on the B-side to “Ivanohé” in 1965. He also participates in the French-Brazilian adventure of Les Masques, with an album that has become a cult item thirty years later. Eddie Barclay once addresses him: “Your thing is gentleness, not bawdy joking. Deal with me and you’ll be able to do whatever you want.”

Within a few weeks, it’s in the bag: three 45s are released by Barclay, along with a first LP, “Amour amitié”, on which he appears sensitive and very forthcoming with stories about himself. First-person lyrics have pride of place on most of the record. He fictionalizes his own life in “On imagine le soleil” with Catherine Philippe-Gérard in the singing role of his wife Marie, in which he weaves the thread of his couple’s memories, or in “Une fille et trois garçons”, a fantasy about a hippie threesome in their living room.

Marie Vassiliu recalls: “At the time we had found an old crumbling farm in Gouverne which required a lot of renovation work. He had more peace and quiet to write better things, poems. There he started partying – a lot – and he took care of the Bilboquet (a café-concert). After that we lost a friend who died in a plane crash. Rough times. We settled in Apt, in a house where we made a swimming pool, constantly full of people: Barclay, Folon, Maria Schneider and her girlfriend… One day, Boby Lapointe dropped by to say hi, we asked him ‘How are you?’, he answered ‘Well, you know, I have cancer, I’m gonna die.’”

Pierre befriends a band of musicians (Bloch-Lainé, Engel…), who are to appear on the records to come. He develops his taste for performing thanks to improvisation, and ends up on the other side, opening spots, venues, bars, restaurants – until the end of his life. This LP has little success, just like the following singles, including “Marie en Provence”; Marie, outraged by this one’s lyrics (in which she appears like a complete sucker), packs her bags. So Pierre creates “Ne me laisse pas” (Don’t leave me) for the flip-side, and Marie comes back. No success either for the second album “Attends”, which includes “En réponse à votre lettre du 2.11.72”, in which he salutes his buddies. He loses Barclay’s trust and now only has the right to record singles, on a quest for a hit. Among them, “Je suis un pingouin” or “Il était tard ce samedi soir” and its now-mythical B-side “En vadrouille à Montpellier”. Three more 45s and finally comes THE supreme misunderstanding: “Qui c’est celui-là”. As he sings it in his autobiographic song “Encore un jour qui passe”: “I made this record above all for its other side”. Namely “Film”, a disturbing boogie in which Pierre relates, in spoken words, a visit to the Bois de Boulogne with whores, trannies and cops, ending at daybreak with the radiant apparition of love, and cadenced by a mantra saying ”I’m still looking for a girl who would have me tonight for a quarter of an hour”. In addition to this gem, the band comes up with the idea of adapting, quick and dirty, a Brazilian song they brought back from a trip, with lyrics churned out somewhere with Marie’s help: “He initially wrote: ‘Who’s that girl’, and I prompted him towards ‘this guy’, which in French was closer to the original sonority.” Barclay sends the single to the radios. Surprise: two big radio stations give the same answer: the B-side is perfect, let’s go for it. Barclay gets the message: “Qui c’est celui-là” becomes the A-side, and Pierre Vassiliu, a funny guy. Millions will be sold, and the label improvises an album made up of the previous 45s.

A dark period follows, during which he finds himself torn between the euphoria of success and its vanity, between the love he gets and the reasons given, between Paris and Provence, between his wife and other women. Marie, too often abandoned and sick of egocentricity, leaves for good; he flees to India, gets lost, reinvents himself and releases a series of three dark, light albums, singing about the decay of humanity, the ravage of alcohol, all-mighty banks, tourists trampling on misery in Africa, breaking up, loneliness, travels and moving houses. But also about his children, a dog, a bird, a pharaoh, and women. Thus his 1976 album features a tribute to his daughter, “Sophie”, and a sad poem about the Earth called “Alentour de lune”. A cracking LP, recorded as a duo at Georges Rodi’s – the top dog of synthesizer – barricaded and high on coke. These three records are commercial failures and put an end to his time at Barclay. In private, everything’s fine, his new wife rejuvenates him, even though he doesn’t lose touch with Marie: “Laura was already in the house when I left for real, he was finally free to live with her. But after every argument he would come back. With Eric [her second husband], they would talk for hours… but never about Eric’s problems.”

This “Laura” period is marked by the singer’s decline of creativity, and by the irruption of Africa into his life. His son Clovis describes this end of a career: “He had written so much material that in the end he kinda went round and round in circles. He mostly earned his living through playing shows, like a real artist, not by selling records. He never sold that much. I have a childhood memory of him calling his impresario on the phone to get the sales figures of his latest record. He hung up looking sad. A thousand and five hundred copies. That was nothing. After the 1980s, that was it. And yet he played at least a hundred shows a year. One of his agents, whom he nicknamed “Miss Cleo”, told me: ‘Your father… I’ve never seen a guy try so hard to ruin his career.’” His 1981 album features “Est-ce qu’on peut voler”, based on a dialogue with then-child Clovis, who poses on the sleeve. “I can remember this conversation but I didn’t discover the song until listening to the album. Likewise, I remember when we took the photo, but he did not tell me this would be for the sleeve. Maybe it was his way of making me a gift. Plus the album’s title is ‘Le cadeau’ (The gift).’”

During the 1990s, his music takes a South-American direction. He hardly releases anything until 2003. “He wanted to have fun. It had even become more important than songwriting. I have fewer and fewer memories of him playing music. Toward the end, he would rather screw around and get wasted. Yet he did ‘Pierres Précieuses’, with a run of only 5,000 copies, co-produced by fans through an association,” Clovis details. This is where “Dis-lui” appears, which we introduced to Marie, at her place in 2016. Paying close attention from start to finish, she commented emotionally: “He sounds all at sea, but of course he’s faking it. He uses anything, anytime, all that happens in his life, in his friends’ life, his children’s life, his wife’s, his women’s…. So it’s great, but… I didn’t expect that.” Pierre Vassiliu dies from Parkinson’s disease in 2015. Clovis: “He actually was a real artist. Even if I never wanted to admit it as a child. There’s something noble. This I didn’t discover before the age of 20. I didn’t see the creative side, the ‘artist’ side, well, the deep side.” A misunderstanding. Bien entendu.

Read Less